By Rabbi Debbie Reichmann

In Numbers 30, a contrast emerges between concise vows made by men and the intricate complexities of vows taken by women. This scriptural exploration delves into the interplay of agency and authority, where a woman’s vow intersects with her father’s or husband’s power to annul it under specific conditions. This interplay, progressive yet bounded, resonates through Torah’s narrative. The text reveals instances of both empowerment and constraint for women, prompting consideration of gender equality’s extent in ancient Jewish society. Comparative insights into historical civilizations underscore the ongoing struggle for parity, mirrored in modern debates like Barbie’s symbolism—a symbol of societal intricacies. Amidst this tapestry, Rabbi Debbie Reichmann’s insight shines, as her study of Torah and Judaism guides a path from history to hope, inspiring transformation. In the evolving landscape of gender equality, Rabbi Reichmann’s steadfast commitment to progress remains unwavering, defying tradition and societal norms.

Chapter 30 of the book of Numbers opens with one sentence regarding a man making a vow: “If a man makes a vow to God or takes an oath imposing an obligation on himself, he shall not break his pledge, he must carry out all that that he has said.” That’s it; no more exposition about the vow of a man. The text then follows with 14 sentences regarding a woman’s vow. Fourteen sentences detailing which man in her life–her father or husband (or sometimes both)–has the power to annul her vow, and in which circumstances.

On the one hand, it is appropriate to highlight the fact that a woman has at least enough agency to bind herself with a vow. On the other hand, what is the value of a vow that is only valid if not nullified by someone else? Sort of progressive, but mostly not? There are many places in the Torah where a woman’s actions or position seems to hew toward a measure of gender equality. In Chapter 27 of Numbers, we learned of Zelophehad’s daughters, four women whose father passed away during the 40 years of wandering in the wilderness with no male progeny. As Moses was distributing land amongst the tribes, the sisters successfully lobbied for ownership of their deceased father’s holdings. Except, the end of that story is found many chapters later, where the women are limited in their inheritance by only being allowed to marry within their tribe.

The Torah gives and the Torah takes away. For every strong and independent woman we read about, there is one that was oppressed, exploited, or denigrated. None of this is news to anyone. As a rabbi, I have often pointed out the places in the Torah and in other Jewish texts where women are painted in a positive light, where they are given agency, and where they have leadership roles and power. I have shared these stories to show that ancient Jewish society was more egalitarian than the ones around them. But, was that really the case?

Common knowledge dictates that throughout history women have been second-class citizens and subject to a whole host of limitations imposed by patriarchal societies. That said, there have been exceptions. Women in the Etruscan civilization (first millennium BCE) were known to have political and administrative power, they were able to participate in public life without being stigmatized. Similarly, women in Spartan society (also first millennium BCE) were educated and could own and inherit property. Granted, both of these are a thousand years after the events of the Torah, but ancient Egyptian society, predating the times of the Torah, had women in some positions of power and respect.

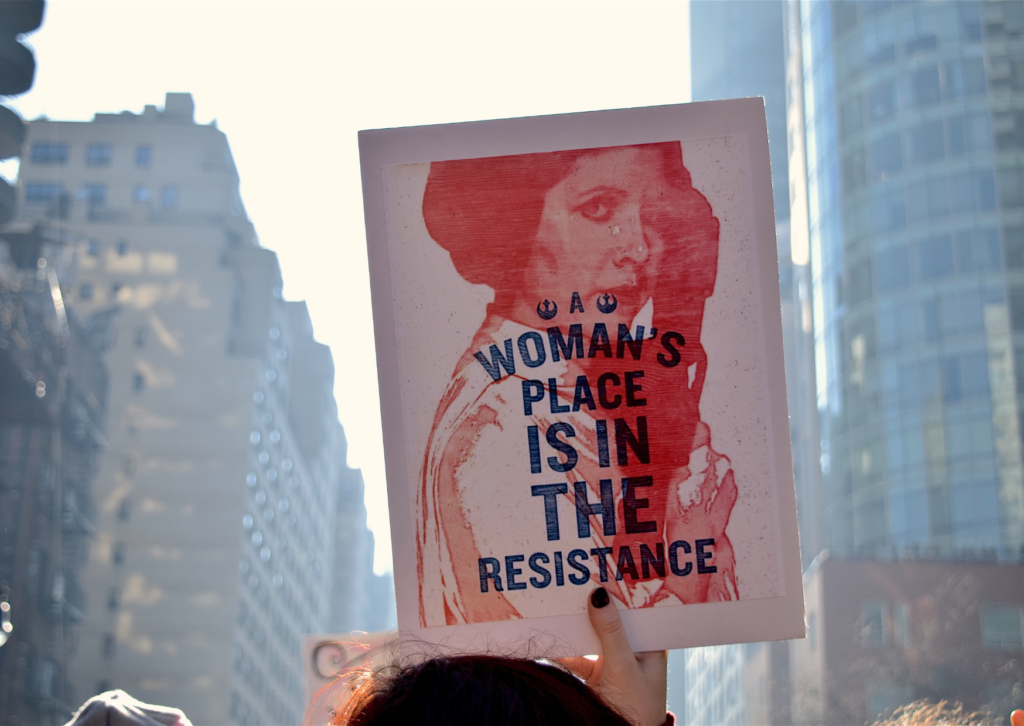

In spite of these societies’ treatment of women, none came close to gender equality. Neither did the ancient Jewish one. And, frankly, neither does ours. This summer’s sizzling debate about Barbie – is she representative of unachievable body standards? Is she a symbol of women’s empowerment? Can she be both? – highlights the tensions in our society and also the distance women’s egalitarianism still has to travel.

Being able to study the Torah and Judaism and see what might have been progressive once and what isn’t now is both eye-opening and ultimately grounds for hope. Even though there are changes that need to be made, the nature of Judaism and its emphasis on learning and analysis gives us the tools to keep those changes coming. If I make a vow to keep fighting this battle, you’d better believe that neither my father nor my husband will annul it, regardless of what the Torah once said.